| |

Eastern Christians cling to their faith as time runs out on the former coal towns of Pennsylvania, reports Jacqueline Ruyak with photographs by Cody Christopulos

Reprinted here with Permission of

CNEWA

Eastern Christians cling to their faith as time runs out on the former coal towns of Pennsylvania, reports Jacqueline Ruyak with photographs by Cody Christopulos

Reprinted here with Permission of

CNEWA

It is the eve of Theophany at St. Mary Protector Byzantine Catholic Church in the northeastern Pennsylvania town of Kingston. Masses of red and white poinsettias frame the iconostasis; the fragrance of beeswax tapers and votive candles fills the air. Father Theodore Krepp celebrates the blessing of water, a purification rite of profound meaning and quiet drama marking the feast of the baptism of Christ. Afterward a hushed congregation lines up to fill bottles with the holy water. “High test stuff,” says an elderly parishioner.

Eastern churches dominate the cityscape of Kingston.

Few of the 100 or so in attendance are children or, for that matter, young. When Father Krepp arrived at St. Mary’s eight years ago, the church had about 275 families. It now has 250, but only 50 children. He points, in contrast, to St. Anne Byzantine Catholic Church in Harrisburg, which was founded in the 1960’s in part because of migration from towns like Kingston; it now has about the same number of families, but three times the number of children. Simply put, demographics indicate that all churches in the region are losing people. With few opportunities locally, almost all the young have left.

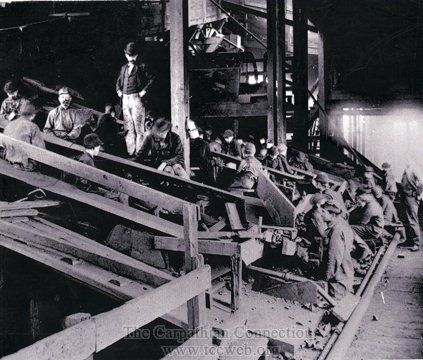

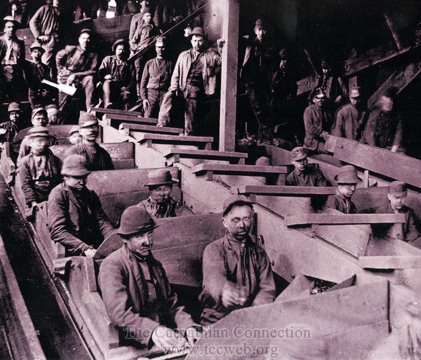

Northeastern Pennsylvania at one time contained three-quarters of the world’s anthracite deposits. The 18th-century discovery of the hard coal – formed over 250 million years ago – later sparked a mining frenzy that would fuel the industrialization of the United States, spur revolutions in technology and create boom towns across the region. Desperate for workers, mining companies scoured Central and Eastern Europe for cheap labor, recruiting many agricultural workers eager to escape the turmoil and poverty of their homeland.

Shenandoah, which sits on the Mammoth coal vein, is home to the gold-domed St. Michaels – the first Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church in the United States.

The immigrants saw opportunity in the dirty, dangerous jobs in the mines. Devoted to their families and churches, these hard-working people shaped the resilient character of the coal region.

But as the country’s energy consumption shifted toward cleaner fossil fuels and the once massive deposits of coal became depleted, the mines began to close. By the late 1950’s, only a few were left, devastating the region’s once vibrant economy and leaving miners without jobs or the skills to compete in a changing labor market.

Garment, shoe and textile factories provided some economic hope in the 1960’s and 1970’s, but they could not compete with rivals in the South and abroad. Consequently, many were forced to leave the region to find jobs. Coal made many towns and for almost a century they thrived, but the closing of the mines sent these towns into a spiraling decline, from which they have never recovered.

One of the oldest Eastern Catholic churches in the United States, St. Mary’s was founded in 1887 to serve Ruthenians. Peasants from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, they came from the Carpathian Mountains, a hardscrabble region now divided among the modern states of Slovakia, Poland and Ukraine. Like many Austro-Hungarians, these people did not have a clear sense of ethnic identity. Their faith, Catholic or Orthodox, set them apart from their neighbors.

Tradition and family, says Father Krepp, have always been central. “Our primary goal, beyond serving the existing population, is to instill the identity of being an Eastern Christian, a Byzantine Catholic, into our youth so they can take it with them when they leave their families. Once that identity was a given. When the church was the center of life, you didn’t have to know a lot about it; it just was. Now if you don’t know what your religious faith is and understand why it is important, it’s just lost when you leave.”

A week after Theophany, Father Krepp is conducting a round of house blessings in the neighborhood. John and Mary Ann Evans share a converted duplex with Mrs. Evans’s 93-year-old mother. A retired social worker, Mr. Evans takes care of his mother-in-law while Mrs. Evans works in their son’s office. Their three children and their grandchildren remain in the area.

Married 50 years, the couple met in the church choir as did many of their friends. From choir and catechism class to caroling and socials, says Mrs. Evans, everything then was “church-involved.”

TV and computers, they agree, have changed life. “You always looked forward to church on Sunday,” says Mr. Evans, “but now everybody seems to have things that are more important.” He worries that, because so many people have left for jobs elsewhere, there are few young adults to assume responsibilities in the church.

Further down the block, Mary Yasenchak, 80, lives next door to her widowed daughter, Mary Ann Mehm. Of Ukrainian background, Mrs. Yasenchak married into the church, while her daughter married out of it only to return after losing her husband in 1996. “It was like I came home because everyone I knew growing up was still there. And they all welcomed me back. It’s like I never left.”

Mrs. Mehm is speaking, however, of her mother’s generation. Most of Mrs. Mehm’s contemporaries have left the area. Of her three children, the youngest is still at home, another remains in the area and the third lives in Brooklyn.

When conversation turns to feast day picnics and piroghi, halupki (stuffed cabbage) and other traditional foods, the two women drift into the kitchen. There spread across the table are homemade bread, kielbasa with horseradish and sweets – cookies and coffee cake, a congenial ending to a house blessing.

Located in the Wyoming Valley, both Kingston with 13,512 residents and neighboring Edwardsville with 4,984 now have declining populations and share a history of catastrophes. In 1959, the Knox mine disaster put an end to mining in the region; in 1972 Hurricane Agnes caused the Susquehanna River to flood, creating one of the most devastating natural disasters the country had ever seen.

Founded in 1911 to serve the then-growing Russian Orthodox community, St. John the Baptist Church is just two blocks from St. Mary’s, and across the tracks, in Edwardsville. Those immigrant Russians were, in fact, from the Carpathian Mountains and Galicia, in what is now Ukraine.

More than half of St. John’s 200 or so parishioners are over 60. To help keep his aging congregation involved, Father Michael Slovesko, called from semiretirement five years ago, is busy overseeing a $300,000 project to install restrooms, as well as an elevator, inside the church. The elevator, he says, will enable wheelchair-bound parishioners to attend church again; it will also make it easier to bring caskets in for funerals.

On a frigid January morning, several parishioners are gathered at the church. Wanda Wanko, 91, who embraced Orthodoxy in 1932, is the oldest; Eugene and Shirley Gingo, in their late 50’s, are the youngsters in the group. The Gingos are unusual in that all their children have opted to stay in the area.

All present remember how it was before people began to leave in large waves, when Edwardsville was a collection of ethnic neighborhoods, but where everyone knew everyone else.

People walked everywhere: to the mines, to visit cemeteries and to go caroling in the town and countryside. They bought their meats and vegetables, their candy and liquor at local stores. They danced and sang, ate and drank at local social clubs. They walked down Main Street, now a dispiriting stretch of marginalized businesses, and saw everyone. Now, those who are left shop at malls.

At the center of it all was the church. “There were a lot of good times that were held from this church,” says one parishioner. “The point is, if there’s no church, there’s no community.”

For the past five years St. John’s has held an annual ethnic food festival, which offers potato pancakes, piroghi, halupki, pigs’ feet, borscht and other favorites. The festival draws people from other churches – even politicians come. So do young people and children. “It’s really very popular,” says Ms. Wanko, “now that they know we have all this good food.”

Some 40 miles southwest of Kingston and Edwardsville lies the town of Shenandoah, which is situated along the Mammoth coal vein. Called the “most magnificent coal bed in the world,” this vein produced over two-thirds of the anthracite mined. Shenandoah was founded in 1866, four years after the first colliery opened, bringing in settlers, eating houses, saloons and more.

Other plants soon followed, and then banks, hotels, boarding houses and tenant houses. In time, three railroads ran into the town. Early settlers were Welsh, Irish and German. Later came the Poles, Ruthenians, Slovaks, Ukrainians, Lithuanians and Italians. Each group settled in their own neighborhoods and, once enough money was collected, each group built impressive churches that resembled the ones they left behind in the Old World. There was a bar on every corner for miners to stop in and “wash the dirt away.” Once the coal mines closed, most of the bars did, too.

In 1915, at its peak, Shenandoah had about 30,000 people. Ripley, in his famed “Believe It or Not” column, once called the town the most congested square mile in the United States. The population is now about 6,000; almost 70 percent are over 60 and 14 percent live below the poverty line.

All the hills surrounding the town have been mined. Massive banks of culm, the waste left after coal screening, are everywhere. Thanks, however, to three cogeneration plants, designed to clean the waste of whatever energy it contains, trees now grow here and there on the culm. In winter, at least, downtown is a disconcerting mix of shabby, sometimes boarded-up buildings and unexpected promise – a ghost perhaps of what used to be.

Seen from high above town, the golden domes of St. Michael Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church still draw the eye. Established in 1884, St. Michael’s is the first Ukrainian Greek Catholic church in the United States. The current church, dedicated in 1984, replaces the original, which was destroyed by fire in 1980. On a morning when the streets are slick with ice and the temperature dips below zero, there are only two women at church.

That afternoon Father Petro Zvarych from St. Michael’s is visiting with three of his parishioners: Nancy Sawka, a recent widow and former bakery owner in nearby Frackville; Andrea Pytak, a retired nurse who volunteers at the rectory; and Samuel Litwak, fresh from a meeting of Downtown Shenandoah Inc., a local group dedicated to the revitalization of downtown.

Mr. Litwak recalls when the main streets were “no different from Manhattan. Shops had the same quality of merchandise as in New York and people were shoulder to shoulder. It was just small town America, and that’s the way it was.”

He has childhood memories, too, of coming to church and not being able to get a seat. The parish now has about 150 families, including about 30 children. Says Ms. Pytak, “In the past three years, we have buried 112 parishioners, and there have been only two or three births a year.”

As in other coal towns, many people have left, while others commute many miles a day to work in Harrisburg, Allentown or Reading.

Father Zvarych, who hails from a small town in Ukraine not unlike Shenandoah, has been at St. Michael’s for less than two years. “It’s a small town, but somehow people are enjoying their lives. What’s nice about this area is that people actually live as a community. They go to church together, they share things together. Something happens and they come to each other, not like in a big town or city.”

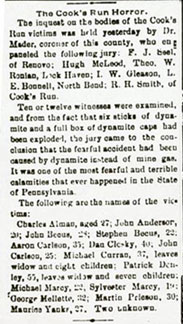

Note: The records of Bitumen are held at the Lock Haven County Court House, St. Joseph's Catholic Church in Renovo, PA, and at St. Mary's Church in Lock Haven. Thanks goes to Teresa Kisko for providing this helpful tip for those researching ancestors from Bitumen.

by, John Martinyak

Courtesy of Robert Smith

Courtesy of Stephen Miller

Courtesy of Steven M. Osifchin

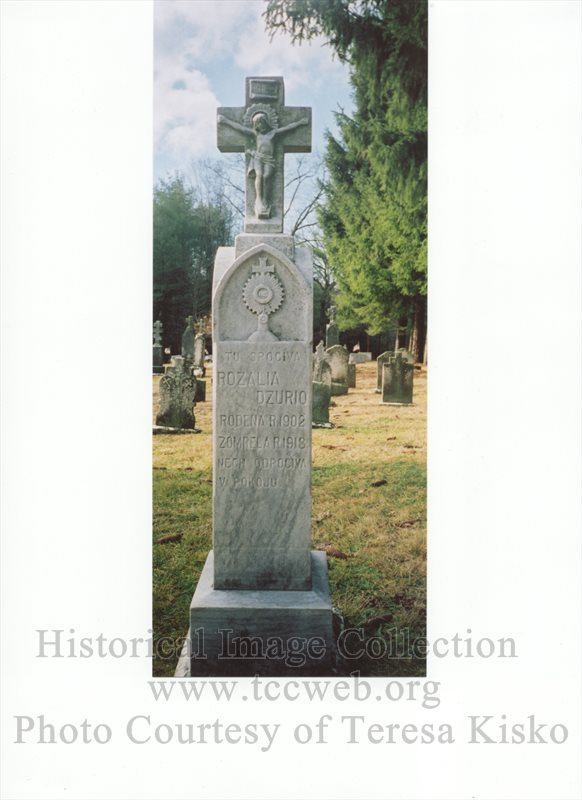

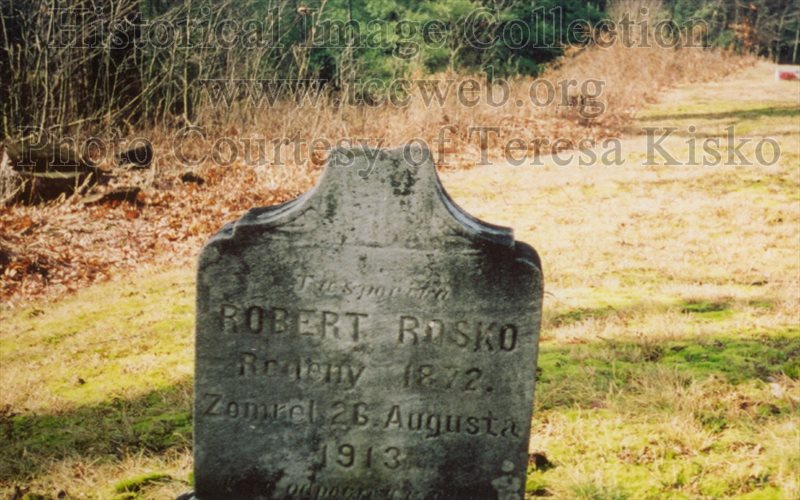

Courtesy of Teresa Kisko

Courtesy of Teresa Kisko

In Memory of the Tomko & the Ronger Families

Bitumen, Pennsylvania

by, John Martinyak

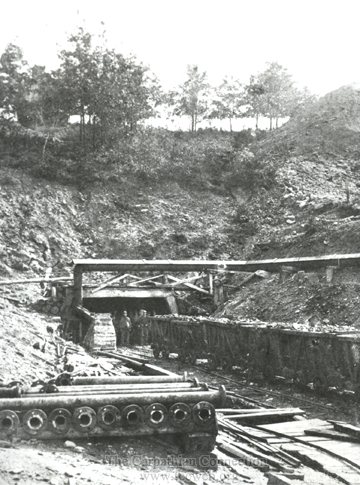

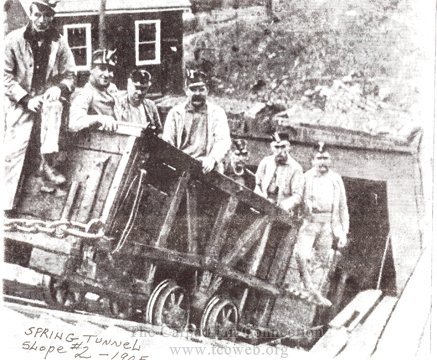

During the later part of the 1800's many people from Eastern Europe decided to immigrate. Many of these immigrants came seeking work and most times, they moved to areas that offered unlimited employment opportunities. This was the case for the town of Bitumen, Pennsylvania. During the years of 1894 to the early 1920's Slovaks came to this town for work, and a new life. It is interesting to scan census figures for this town as it was mostly populated by Slovaks outside of a some individuals of Swedish and Ruthenian heritage. The main attraction for this town was the Kettle Creek Coal Company. This mill offered vast employment opportunities for the new immigrants. Even though the work was dangerous and hard, the jobs were abundant and steady. Bitumen revolved totally around the Kettle Creek Coal Company. Residents lived in company owned homes and shopped in company owned stores as was the practice in some states, especially Pennsylvania and West Virginia. This company had the entire town in its control. If an individual wished to purchase goods from another town, or a Sears Catalog, the company would not permit the delivery of such items. The residents had no choices and were dependent upon local stores. Not only in commerce but also, there was a company doctor who cared for the residents. The review of historical documents shows one doctor was named Dr. Mervine and he treated not only the accident cases in the mines but took care of all other medical needs in the community. Payment of the doctor could take many forms as these immigrant residents had very little financially. Many residents of Bitumen had their own vegetable gardens and some small livestock and poultry. It was not uncommon for a resident to pay the doctor with a chicken, or a basket of tomatoes. These gardens also helped the immigrants to stretch their paychecks and help keep their bill at the company store lower.

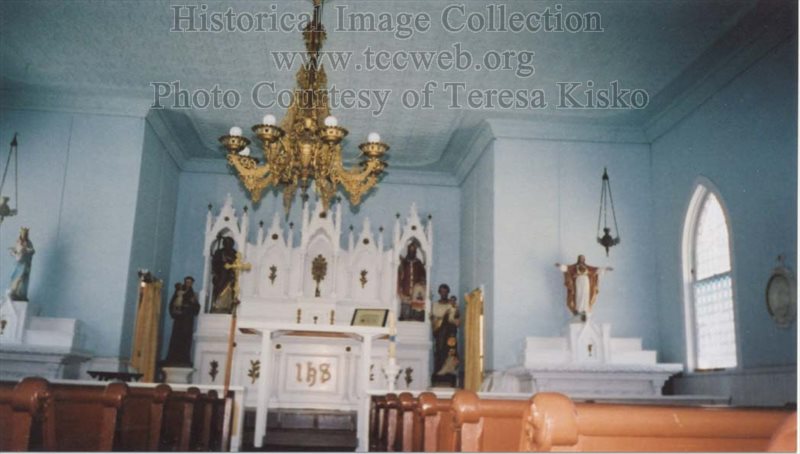

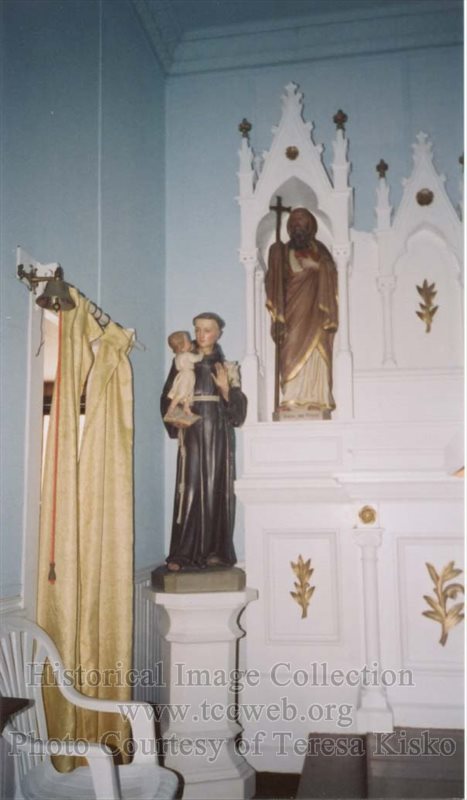

After the immigrants had settled in Bitumen the need for a church became necessary. In 1897 with funding from The First Catholic Slovak Union (Jednota), Immaculate Conception Slovak Roman Church was built to serve the immigrants spiritual needs. The church was moved several times due to constant expansion of the Kettle Creek Coal Company to where it finally stands today. This church is a wooden, clap-board frame design and is similar to many un-adorned Protestant architectural churches in the region. This church also started a school for its children. Studies in grammar, mathematics and history were combined with religious instruction. The Vincentian Sisters of Charity were called upon to staff the school and teach its pupils. Classes in the Slovak language were also taught to the children as in town it was more common to hear Slovak than English in the shops and stores. Not only were Slovak Roman Catholics members of Immaculate Conception but also, those Slovaks (and some Ruthenians) of the Greek Catholic church attended services.

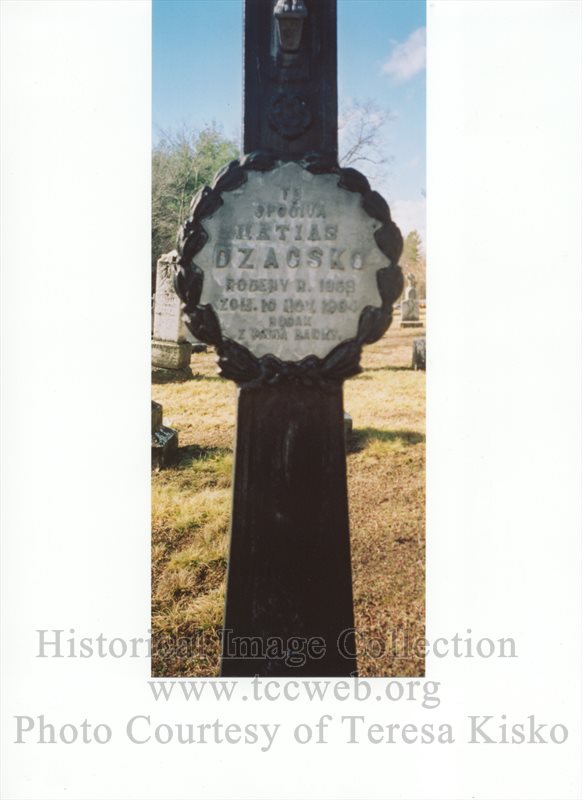

The cemetery that is located next to the church shows old grave stones which are not only Roman Catholic but also Greek Catholic (an Eastern Rite). These Greek Catholics can be identified by their distinct three bar crosses. As time progressed a local public school was added and this was beneficial to residents who could not afford the small tuition to the Catholic school. Bitumen grew as more and more immigrants came due to letters from their families telling them that jobs were available. The town started to take on an atmosphere such as that found in any remote Slovak village. People refrained from work on holy days and had processions in the streets. A band was organized which played on these days and for American holidays and celebrations. Dancing was also an important social function and the town would eventually build two dance halls which would sponsor various events for the public. Also constructed was a Slovak Hall which would be the seat of two Slovak fraternal organizations. Many people in Bitumen had limited financial resources and therefore, had to find forms of entertainment which had no financial requirements. Baseball games were very popular as were picnics and long walks after the Sunday meal.

During the period of World War I the town continued to expand. When America entered the war in Europe many companies in the United States decided to cut their workers salaries. The Kettle Creek Coal Company also implemented this practice. Many of the workers saw their salaries cut while doing the same long hours of work. This practice was to cause much dissent in Bitumen and in other towns and cities throughout the United States. Many immigrant males decided to join the service rather than work for less wages. Joining the service also offered one advantage which they did not have in their home towns. It would offer them an easier way to become American citizens and many joined voluntarily throughout the United States. In Bitumen, the Slovak immigrants banded together and refused to take a cut in their salaries. Being a union mine, the company let their contract expire and then refused to open again. The miners then went on strike and the company brought in new workers to staff the mine. These were times filled with tension as war fever had become prevalent in the United States. Striking was seen as un-American and at its worst, treason. Many striking miners were evicted from their company owned homes and this was a great hardship for many. Company and local police constantly patrolled not only the Kettle Creek Coal Company property but, the town itself as they felt they not only owned the mine, but, the town as well. As the strike progressed and people lost their homes, many decided to leave Bitumen. Relocating was common to other cities and towns where relatives lived or where friends told them of employment opportunities. One place which many residents migrated to was Trenton, New Jersey. Trenton at this time offered many benefits over Bitumen, the best being New Jersey had outlawed the company store and home practices soon after the turn of the century. Trenton’s employment base was expanding due to its region. Mines and mills of coal or other based fuel products were not the main base in New Jersey. The manufacturing and production of goods and textiles was always needed and Trenton had large abundance of these companies.

When the strike finally ended many saw no reason to stay in Bitumen. The company had won the day and many families had suffered terribly. When the Kettle Creek Coal Company opened again for full production, many refused to return to their jobs which now had their salaries set at a lower rate. This was the beginning of the demise of Bitumen. As each month came and went, more and more families packed their belongings and compiled their financial resources to leave. The church was a good indication of the numbers who left as the membership began to decline very seriously. The parochial school which had been started at Immaculate Conception Slovak Roman Catholic Church had to be closed. With few students to teach the Vincentian Sisters of Charity left as they were not needed any longer. More and more individuals left Bitumen as word came back from former neighbors of the opportunities in other states and towns. The membership of the church fell so low that it was finally made a mission church for Saint Joseph’s church in nearby Renovo. Things became so desperate that it was suggested the church be dismantled. The few remaining members of Immaculate Conception in Bitumen banded together and petitioned the Altoona-Johnstown Roman Catholic Diocese not to do this. By 1969, the members of the church and new residents of Bitumen continued to ask the Diocese to keep the church open. They wished to preserve the church as it was not only a house of worship, but, a historical part of Bitumen and turn of the century immigration. It was decided to turn the church into a shrine and residents and members began the Bitumen Shrine Corporation to protect and maintain the church and cemetery. Collections and donations were received and the church was renovated. Today, this church is totally dependent upon donations for its upkeep and maintenance.

Not only those from Bitumen but others have given of their time and talents to keep this church maintained and functioning. An individual from Renovo took an entire summer by himself and restored the crucifix in the church yard. Many other residents of Bitumen have continued to support and maintain the grounds and church structure. During each Fourth of July weekend there is a reunion held in Bitumen at Immaculate Conception Shrine. Former residents, present residents, friends and supporters gather at this Shrine to see each other and participate in a mass. It is to the credit of the present day residents of Bitumen and all those who are helping to preserve this piece of immigrant history. This small, white clap-board church is a historical delight and one of the very few glimpses into the immigrant experience. The cemetery is also an historians pleasure as many of the stones are very old and have great ethnic historical value. The cemetery, being right along side of the church reminds a person of the villages in Eastern Europe where this practice is seen. It is very uncommon today to find a church which has a cemetery attached to it and especially, one that was begun and almost totally filled with one particular ethnic heritage. Inside the church, the altar is graced by statues of SS. Cyril and Methodius which are honored saints by the Slovak people. This church has seen history in the making and its members labored hard to build and support it. It is a monument to the founders of Immaculate Conception and also to the residents who helped build the town of Bitumen. For those who travel in this area of Pennsylvania, this town is not to be missed as the experience will make a deep impression on the visitor for a very long time.

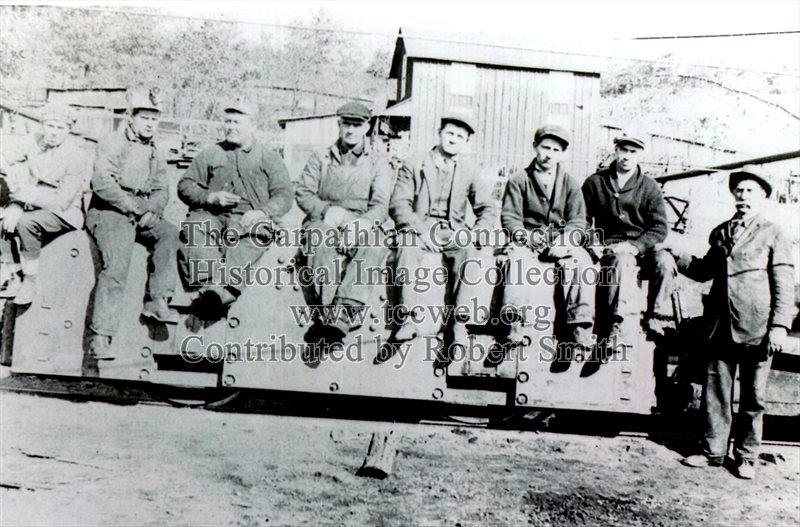

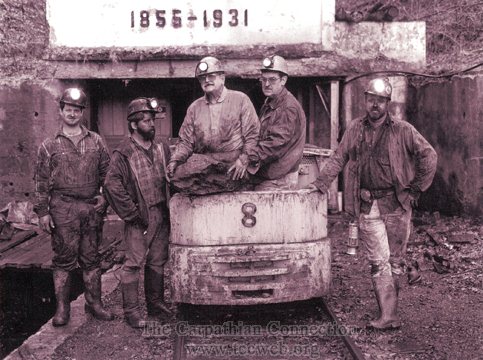

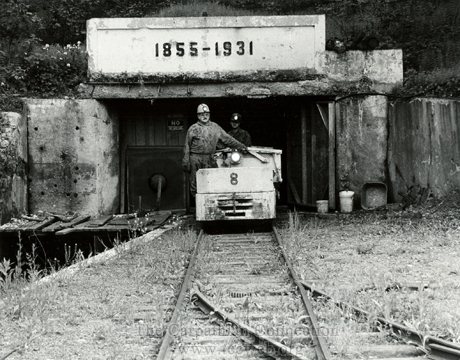

Courtesy of Robert Smith

Bitumen miners sitting on a "mantrip". The second man from the left John Ronges (Rondos, Ronyges, Ronges, Rongers) Robert's Grandfather

Photos Courtesy of Steven M. Osifchin

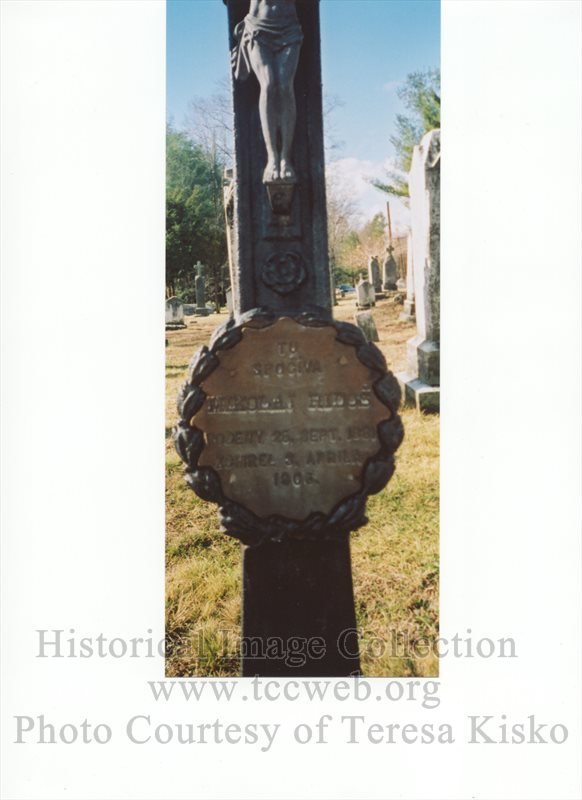

Courtesy of Teresa Kisko

Courtesy of Teresa Kisko

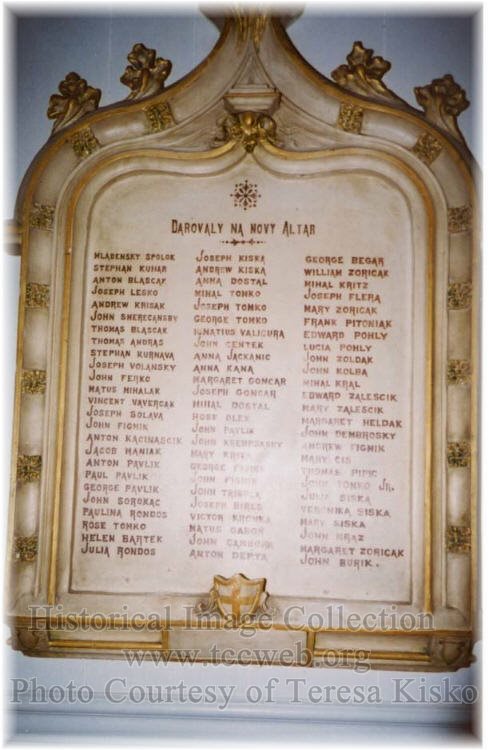

Dedication Plaque Located in the Church Entry

Names found on Plaque

-

Mladensky Spolok

-

Stephan Kunar

-

Anton Blascaf

-

Joseph Lesko

-

Andrew Krisak

-

John Smerecansky

-

Thomas Blascak

-

Thomas Andras

-

Stephan Kurnava

-

Joseph Volansky

-

John Ferko

-

Matus Mihalak

-

Vincent Vavercak

-

Joseph Solava

-

John Fichik

-

Anton Kacinascik

-

Jacob Maniak

-

Anton Pavlik

-

Paul Pavlik

-

George Pavlik

-

John Sorokac

-

Paulina Rondos

-

Rose Tonko

-

Helen Bartek

-

Julia Rondos

-

Joseph Kiska

-

Andrew Kiska

-

Anna Dostal

-

Mihal Tomko

-

Joseph Tomko

-

George Tomko

-

Rinatius Valicura

-

John Centek

-

Anna Jackanic

-

Anna Kana

-

Margaret Concar

-

Joseph Concar

-

Mihal Dostal

-

Host Olex

-

John Pavlik

-

John Kelmpsasky

-

Mary Kritz

-

George Figmik

-

John Figmik

-

John Trivula

-

Joseph Bires

-

Victor Kromka

-

Natus Gabor

-

John Cambora

-

Anton Depya

-

George Begar

-

William Zoricak

-

Mihal Kritz

-

Joseph Flera

-

Mary Zoricak

-

Frank Pitoniak

-

Edward Pohly

-

Lucia Pohly

-

John Zoldak

-

John Kolba

-

Mihal Kral

-

Edward Zalecsik

-

Mary Zalecsik

-

Margaret Heldak

-

John Dembrosky

-

Andrew Fignik

-

Mary Cis

-

Thomas Pipic

-

John Tomko, Jr.

-

John Siska

-

Veronika Siska

-

Mary Siska

-

John Mraz

-

Margaret Zoricak

-

John Burik

In Memory of the Tomko & the Ronger Families

Swanson & Anderson Photographers, Bitumen, PA.

Searching for information on Jan Nadaský. He was an Uncle on my Mother's side. He left Nagy Brestovany (now Velke Brestovany) Slovakia in former Nitra County today Trnava County in summer of 1912 and lived in Bitumen, Penna. In March 1913 his leg was broken in a mine accident and he stayed with out a job. The last letter our family received from him was in April 1913. He was asking for money for his return trip home. In June 1913 our family sent money to him at Box 117, Bitumen, PA, Clinton County, USA. This information was garnered from two old letters and an old money order confirmation. The family never heard from him after that last letter. Jan may have had a cousin living in Penna named Joseph Turansky. This is a photo from right to left of his wife Agnesa, son Stefan, and son's wife Agnesa sometime in the 1950's. Thank you, Mario Veneni.

Contact: Mario Veneni

Compiled Listing of Slovak Immigrant Surnames

Courtesy of John C. Orsulak

Compiled List of Marriages 1882 - 1903

Courtesy of John C. Orsulak

by, David Kuchta

History Courtesy of Rev. Thomas A. Derzack, Mr. Paul J. Hackash and Mr. John C. Orsulak. Photo Courtesy of Doctor Bob Valent

Compiled Listing of Slovak Immigrant Surnames Courtesy of John C. OrsulakThese files requires that you have Adobe Reader installed on your computer in order to view the files.

NOTE: Earliest Marriages 1888 to 1903 have no villages listed and some may be cross referenced under "Additional Surname Listing."Many Marriages took place in Slovakia or elsewhere. These names may be listed under "Additional Surname Listing."Maiden Surnames of Deceased listed under "Recorded Deaths", may be cross referenced under "Additional Surname Listing", using Spouse surname.

Summit Hill, Pennsylvania

Recorded Slovak Marriages

Indexed by Year of Marriage, 1882 - 1889

No Village of Origin Listed

1882 Komar Steve / Jumbar Anna

1883 Kolesar Michael / Kamenicky Anna

1884 Juskanic Michael / Durkos Mariam

1884 Kusnerik John / Forgach Mariam

1884 Metro Paul / Hruska Anna

1884 Sotak Paul / Tomasko Anna

1886 Dennis Michael /Stofko Mariam

1886 Kulko John / Stelmach Mariam

1886 Lesko John / Solak Anna

1886 Matta John / Hrobovcak Anna

1886 Matta Joseph / Martin Maria

1886 Ochran Michael / Lupco Elizabeth

1887 Dolak Andrew / Hruska Maria

1888 Frendak Michael /Cmil Anna

1888 Jonosco H. / Kamenicky Maria

1888 Jevcak John / Kuta Anna

1888 Jevcak Andrew /Tomasko Ella

1889 Frendak Paul / Caky Mariam

1889 Hrobovcak John / Kulka Susanna

1889 Maruscak John / Rusnak Maria

1889 Matta John / Hudak Ilona

1889 Sniscak John /Jevcak Susanna

Jim Thorpe, Pennsylvania

Recorded Slovak Marraiges

Indexed by Year of Marriage, 1892 - 1895

No Village of Origin Listed

1892 Sabol Steve / Kosaj Maria

1892 Skrabak Paul / Tomanek Agnes

1892 Torht Andrew / Lesko Maria

1892 Varjov John / Markus Maria

1893 Adamec Ignatz / Janacek Terezia

1893 Franko Andrew / Kovac Anna

1893 Gross Joseph / Hnat Anna

1893 Granat John / Vojacek Anna

1893 Gajdos Andrew / Rujak Maria

1893 Kamenicky Andrew / Regina Maria

1893 Metro Michael / Isvar (Zebian) Anna

1893 Ringer Steve / Lupco Lucia

1893 Sopcak Jan / Lendarak Elizabeth

1894 Jevcak Henricus / Knies Anna

1894 Kanich John / Sich Magdalena

1894 Kerestes Michael / Gasho Maria

1894 Koribsky Joseph / Skavaria Anna

1894 Kuritz Albert / Gorka Sophia

1894 Kulka George / Kolesar Anna

1894 Marzin George / Pozen Ersa

1894 Novak Florian / Repa Rosa

1894 Rujak John / Harakal Susanna

1894 Stajanca Andrew / Baran Elizabeth

1894 Sedila John / Kovcin Ella

1894 Shuhida John / Hruska Susanna

1894 Sotak John / Sokal Maria

1894 Vida Joseph / Jurasko Maria

1895 Jackovac Michael / Chuch Maria

1895 Jantosik Joseph / Porvaznik Mary

1895 Kanich Michael / Goutach Catherine

1895 Lupco George / Frendak Elizabeth

1895 Lukac Paul / Valek Maria

1895 Madak Paul / Zich Anna

1895 Posta John / Zabrosky Anna

1895 Pekarik Michael / Pavelko Anna

1895 Zaleha Joseph / Marcinko Maria

Jim Thorpe, Pennsylvania

Recorded Slovak Marriages

Indexed by Year of Marriage

1890 - 1892 / 1895 -1903

No Village of Origin Listed

1890 Chehit Martin / Pavelko Maria

1890 Martin Michael / Pavelko Mariam

1890 Pazo John / Porvaznik Susanna

1890 Zaleha Michael / Kutcher Maria

1891 Dicky John / Saxon Anna

1891 Domas Daniel / Polak Anna

1891 Jacobs Michael / Sabol Anna

1891 Jensura Michael / Potosnak Maria

1891 Kasrarek George / Zebiak Anna

1891 Koltiska Paul / Komar Mariam

1891 Kulha Paul / Pelc Elona

1891 Margevic Michael / Zaleski Josephine

1891 Papane John / Kutlat

1891 Sopko Paul / Bednar Mariam

1891 Zupko Michael / Vytek Mariam

1892 Adamcik Michael / Porambo Maria

1892 Varjov John / Markus Maria

1894 Vida Joseph / Jurasko Maria

1895 Hodek Joseph / Vitek Tereza

1895 Severnak Stefan / Kakos (Isvar) Maria

1895 Velicky Joseph / Orsulak Elizabeth

1896 Cupa Peter / Stelmach / Maria

1896 Figura Peter / Vitek Julia

1896 Hakac Paul / Polesnak Matilda

1896 Hlavaty Raphelus / Hutta Elizabeth

1896 Krajcirovic Michael / Rusnak Elizabeth

1896 Lantos Joseph / Ondrus Magdalena

1896 Lantos Michael / Simek Terezia

1896 Leskovsky Martin / Bilka Elizabeth

1896 Martin John / Sotak Anna

1896 Matta Michael / Hrobovcak /Maria

1896 Pollak Wash / Dresho Susanna

1896 Rohal John / Matta Maria

1896 Sudy George / Porvaznik Ilona

1897 Bednarik Michael / Caky Susanna

1897 Chuchran Andrew / Krestanka

1897 Franko Andro / Kovac Anna

1897 Hlavaty Joseph / Vojacek Susanna

1897 Janicek Joseph / Jurik Maria

1897 Kendra Joseph / Hager Maria

1897 Koliba John / Cesarik Ella

1897 Kumancik Martin / Uher Anna

1897 Moravek Vitus / Kukan Katerina

1897 Pavelko John / Pekarik Tereza

1897 Sabol John / Juhas / Maria

1897 Tokos Izidore / Hironka Sophia

1897 Wostak Paul / Hudak Anna

1898 Blichar John / Sudej Anna

1898 Bolojac Paul / Valorcik Maria

1898 Hajura Joseph / Hrobovcak Susanna

1898 Lapos John / Heger Anna

1898 Rujak John / Jevcak Anna

1898 Sotak George / Mihalko Anna

1898 Velicky Michael / Vitek Magdalena

1899 Dicky Andrew / Majernik Anna

1899 Dicky Joseph / Majernik Maria

1899 Janacek Valentine / Ondrus Maria

1899 Kebles John / Kerestes Elizabeth

1899 Smolinsky Mathias / Jurovaty Anna

1899 Stehlik Joseph / Lisicky Maria

1900 Cepa Paul

1900 Dresak John / Matiasovic Maria

1900 Fillipovic Joseph / Krusek Maria

1900 Hivko Steve / Hnat Susanna

1900 Holic John

1900 Januska John / Surjak Anna

1900 Kenderes John / Mesaros Maria

1900 Kocerha Michael / Frendak Elizabeth

1900 Kostelnik Joseph / Kovac Catherine

1900 Kuharsky Andrea / Brus Maria

1900 Lisicky John / Petras Anna

1900 Lisicky Martin / Krajcirovic Rosa

1900 Lukash Martin / Valuch Martha

1900 Marik John / Puska Susanna

1900 Micak George / Zap Margarita

1900 Osinkovsky John / Repko Anna

1900 Potocky John / Stajanca Antonia

1900 Serina Simon / Odehnal Katerina

1900 Shubak George / Majernik Elizabeth

1900 Skrabak Joseph / Radocha Maria

1900 Tkac George / Mihalko Maria

1900 Uher John / Odehnal Frantiska

1901 Bednar George / Stofko Anna

1901 Bucko George / Kamenicky Anna

1901 Haluska George / Berta Elizabeth

1901 Hrosen Gaspar / Pavlik Christina

1901 Jevcak Henricus /

1901 Kafana John / Kratky Rozaria

1901 Kosich Andrea / Matta Anna

1901 Marcin Joseph / Komar Maria

1901 Marcin Michael / Berila Maria

1901 Matsick George / Hivko Maria

1901 Ochran John / Rohal Maria

1901 Oravec Florian / Krajcirovic Maria

1901 Pavlik Andrea / Marcinko Anna

1901 Pavlik John / Skrabak Maria

1901 Pavlik Michael / Skrabak Frantiska

1901 Pekarik John / Hadvabni Susanna

1901 Peltz Latzie / Pastor Maria

1901 Petras John / Ochranek Maria

1901 Rohal George / Homash Anna

1901 Smolinsky Andro / Kumancik Maria

1901 Sotak Alex / Cipka Maria

1901 Urbanec George / Petras / Maria

1901 Vanich Stefan / Yurik Maria

1901 Velicky Paul / Hlavaty Helen

1902 Burran Stefan / Romanek Rosa

1902 Gaza Stephen / Hamrlik Christina

1902 Goisco Michael / Kenderes Maria

1902 Hager John / Komar Anna

1902 Hutta Stefan / Oravec Julia

1902 Marcinko Paulus / Oracko / Maria

1902 Porvaznik Andrea / Wasko Anna

1902 Repko Joseph / Zurkutz Anna

1902 Sekalik Michael / Marcinko Maria

1902 Shruba John / Flyzik Maria

1902 Skuty Michael / Zaleski Ella

1902 Vitek Simon / Lantos Maria

1902 Ziskay Sandor / Kukan Katernia

1903 Barasovsky Vendelin / Holkovic Eliz.

1903 Bilka Stefan / Lukac Elizabeth

1903 Cipko Joseph / Urbanec Maria

1903 Gajdos Andrew / Babinec Maria

1903 Gambala John / Liptak Veronica

1903 Jursa Petrus / Petras Maria

1903 Kralicek Joseph / Kukan Christina

1903 Matula Paulus / Ondrus Anna

Stability Instead of Decline100th Anniversary CelebrationLansford, Pennsylvaniaby, David Kuchta

In today's society, many churches are closing their doors or the membership is merging with other churches. Because of dwindling membership or the lack of interest among church goers, many churches are becoming an empty shell. Some are left to deteriorate or in some cases, just torn down. In Lansford, there is St. Johns Slovak Lutheran Evangelical Church, whose membership just celebrated their 100th anniversary of its founding. In the early days, some of the Slovak membership worshiped at Trinity Lutheran Church in Lansford. In celebrating the 100th anniversary they have once again turned to Trinity Lutheran Church for the use of their pastor.

The Slovak Lutheran immigrants who came to the Panther Valley in the late 1800's to work in the coal mines found that they had to utilize other churches for a place of worship. On February 22, 1899 they met with the Rev. Ludvi Kavel, pastor of the Mt. Carmel congregation, who became the first administrator of St. Johns, to form their own church. The sad part is that there is no written records of that very first meeting. But through some of the Church Founder’s recollections, it was known that the first meeting was held in the so-called Neumuller's Hall, located on the corner of Ridge and Center St. in Lansford. There were 36 members present on that day. Just like anything else in life, deciding on a meeting place among its members caused the first rift, splitting it into two groups. One group wanted to worship in the Trinity Lutheran Church and the other in Nemuller's Hall and then later in the English Congregational Church, all in Lansford.

What happened is the members paid rental fees to both organizations. They paid the Trinity Lutheran Church, $60 a year rental and the other group paid $25.00 a year for Nemuller’s Hall. To the early immigrants this was a lot of money. We have to remember that the mine labors at that time got about eight cents an hour. Because of this they started making plans to build a church of their own. Every working member offered to give a day's wages, once a month, for a year to the building fund. Four members loaned money, interest free and because of this the building started. I'm proud to say that my Grandfather, George Zlock, was one of the four members to loan money to the church. My other grandfather, Frank Bayer, was one of the "Founding Fathers." In the fall of 1903, the church was well on its way to being built and on November 15, 1903, there was the first dedication of the corner stone. Being unable to afford a Slovak pastor that day, The Rev. Charles J. Gable of Trinity Lutheran Church was invited to take charge of the dedication. The singing of hymns were all in Slovak. We must remember that many of these immigrants could only speak Slovak and some didn't understand English. Rev. Gable didn't understand or speak Slovak. But through the grace of God, the dedication went forth. St. Johns was completed on May 30, 1904, a tremendous triumph for the new congregation! The dedication was performed in a manner befitting the occasion with three Slovak pastors present, all from neighboring churches of Mt. Carmel., Mahanoy City and Nanticoke. Still unable to afford their own pastor, Rev. Charles J. Gable again agreed to do the dedication. What happened is the members paid rental fees to both organizations. They paid the Trinity Lutheran Church, $60 a year rental and the other group paid $25.00 a year for Nemuller’s Hall. To the early immigrants this was a lot of money. We have to remember that the mine labors at that time got about eight cents an hour. Because of this they started making plans to build a church of their own. Every working member offered to give a day's wages, once a month, for a year to the building fund. Four members loaned money, interest free and because of this the building started. I'm proud to say that my Grandfather, George Zlock, was one of the four members to loan money to the church. My other grandfather, Frank Bayer, was one of the "Founding Fathers." In the fall of 1903, the church was well on its way to being built and on November 15, 1903, there was the first dedication of the corner stone. Being unable to afford a Slovak pastor that day, The Rev. Charles J. Gable of Trinity Lutheran Church was invited to take charge of the dedication. The singing of hymns were all in Slovak. We must remember that many of these immigrants could only speak Slovak and some didn't understand English. Rev. Gable didn't understand or speak Slovak. But through the grace of God, the dedication went forth. St. Johns was completed on May 30, 1904, a tremendous triumph for the new congregation! The dedication was performed in a manner befitting the occasion with three Slovak pastors present, all from neighboring churches of Mt. Carmel., Mahanoy City and Nanticoke. Still unable to afford their own pastor, Rev. Charles J. Gable again agreed to do the dedication.

Festivities began with a procession through the streets of Lansford. In the lead were three church officers on horseback, followed by two horse-drawn carriages with the visiting clergy, a band, local and neighboring units of Catholic fraternal organizations with banners, and then friends and members of the congregation. The procession ended at the outside of the church, around the corner-stone, singing two verses of a hymn from their European Spevnik, the Kyrie and then the response. Then they began entering the sanctuary for the service singing the last two verses of the hymn. Now on to the present: St. Johns Slovak Lutheran Evangelical Church thought it befitting to recreate the dedication of the church. This time Rev. John Keiter, Pastor of the Trinity Lutheran Church, officiated. Although the re-enactment was done in English, Rev. Keiter gave the Kyrie in Slovak. I'm almost certain that if the founding fathers were looking down on this festive occasion, they were well pleased with Rev. Kieter’s attempt at the Slovak language. This time, at the end of the service, a small group marched up Abbott St. to the Trinity Lutheran Church. No horses, bands or horse-drawn carriages. Instead of the band it was led by a trumpeter and parish son, Edward Kalny, now of New York. Several of the marchers wore folk clothing that represented parts of their ancestral homelands of Slovakia. This folk clothing or "Kroj," as they are called, depict our heritage and are the way our founding fathers and parents dressed for special occasions, before coming to America. Yours truly, dressed in a Slovak Folk outfit also carried the Slovak flag in commemoration of my ancestor's homeland When arriving at the Trinity Lutheran church, Pastor Keiter, led us into the church and then down into the meeting room where Ann Trauger, President of St. Johns Church Council, gave a small speech, thanking the people of the Trinity Lutheran Church for the help in those early years when the church was first founded. Festivities began with a procession through the streets of Lansford. In the lead were three church officers on horseback, followed by two horse-drawn carriages with the visiting clergy, a band, local and neighboring units of Catholic fraternal organizations with banners, and then friends and members of the congregation. The procession ended at the outside of the church, around the corner-stone, singing two verses of a hymn from their European Spevnik, the Kyrie and then the response. Then they began entering the sanctuary for the service singing the last two verses of the hymn. Now on to the present: St. Johns Slovak Lutheran Evangelical Church thought it befitting to recreate the dedication of the church. This time Rev. John Keiter, Pastor of the Trinity Lutheran Church, officiated. Although the re-enactment was done in English, Rev. Keiter gave the Kyrie in Slovak. I'm almost certain that if the founding fathers were looking down on this festive occasion, they were well pleased with Rev. Kieter’s attempt at the Slovak language. This time, at the end of the service, a small group marched up Abbott St. to the Trinity Lutheran Church. No horses, bands or horse-drawn carriages. Instead of the band it was led by a trumpeter and parish son, Edward Kalny, now of New York. Several of the marchers wore folk clothing that represented parts of their ancestral homelands of Slovakia. This folk clothing or "Kroj," as they are called, depict our heritage and are the way our founding fathers and parents dressed for special occasions, before coming to America. Yours truly, dressed in a Slovak Folk outfit also carried the Slovak flag in commemoration of my ancestor's homeland When arriving at the Trinity Lutheran church, Pastor Keiter, led us into the church and then down into the meeting room where Ann Trauger, President of St. Johns Church Council, gave a small speech, thanking the people of the Trinity Lutheran Church for the help in those early years when the church was first founded.

Trauger finished off her presentation with the following: Today, a hundred years later, history has strangely repeated itself. As we were in May of 1904 without a pastor, here we are again, without a pastor of our own, and back to the Trinity Lutheran Church for a pastor, were we first started. We have come full circle, and the thread in the tapestry of life binds us together once more. She thanked the Trinity Lutheran members for allowing them to share this special day with them. I myself was honored to be invited, to partake of the re-enactment of the dedication and founding of the church where I was baptized. It's good to see churches celebrate anniversaries instead of church closures.

Lansford, Pennsylvania

Over a Century of Faith & Slovak Heritage

"Viera a Dedicstvo"

The Carpathian Connection would like to offer our deepest appreciation to Rev. Thomas A. Derzack, Mr. Paul J. Hackash and Mr. John C. Orsulak who have provided us with this history. We'd also like to thank Doctor Bob Valent for providing us with a photo of St. Michael's.

A Review of St. Michael's First 100 Years: A Review of St. Michael's First 100 Years:

In 1881, six men accepted the invitation of Mr. Eckley B. Coxe, a coal operator, to come to Pennsylvania to work in the anthracite "hard coal" mines. These men were Slovaks-the first Slovak Catholics of Lansford. On September 21, 1890, a fraternal society for Slovaks of this vicinity was organized at the Lansford Opera House. This benevolent organization of St. Michael placed itself under the protection of the Sacred Heart. The occasion marked the emergence of Slovaks from the shadows to which they were driven by their suspicious neighbors because they spoke a strange language and practiced unfamiliar customs.

In May, 1891, the Rev. William Heinen, Pastor of St. Joseph Parish in East Mauch Chunk, was passing the home of W.Z. Zehner, superintendent of mines, when the gardener addressed him. We recognize this caretaker as Mr. Michael Provaznik, who played a pivotal role in the affairs of the incipient parish. During their conversation, the talk turned to the erection of a church for the exclusive use of Slovak immigrants who settled in the Panther Valley area.

It was late June of that year when Fr. Heinen called a meeting of the Slovaks, again in the Opera House. Prior to the meeting, he canvassed the whole vicinity, personally inviting the people to the scheduled conference. All went well regarding the formation of the Slovak parish until Fr. Heinen informed the gathering that a plot of ground for the proposed church would cost about $300, with a further expenditure of $3,000 for an unfurnished church. The people were more than a little hesitant, for those were the days when a miner received 90 cents for nine hours of back-breaking labor. This drawback and other difficulties vanished before the intense desire to have a Slovak Catholic Church wherein they would once again hear the word of God in their beloved mother tongue. The members of the newly-formed parish decided to place their trust in the patronage of Saint Michael the Archangel.

Construction of Original Church Begins:

A wooded section on the southern edge of town was purchased by Fr. Heinen from the Lehigh Coal and Navigation (L.C. & N.) Company, a plot of ground 150 by 50 feet for $150. On July 18, after the men of the new parish cleared the land, the congregation began soliciting bids for the erection of a frame church structure 35 by 65 feet. Two weeks later, the contract was awarded at a cost of $2,450.

While the first church of St. Michael the Archangel was being constructed, the parishioners of the fledgling parish attended St. Joseph Church in nearby Summit Hill. Fr. Heinen had obtained permission to celebrate Mass in the Slovak language at 6:45 AM or at 12:45 PM on alternate Sundays.

Working at a feverish pitch, within a month it was possible to lay the cornerstone on Sunday, August 30, 1891. Building operations progressed so rapidly that on Sunday, December 20, 1891, the Slovak people of the Lansford and the surrounding Panther Valley area saw the realization of their dreams and the fulfillment of their hopes. The air was crisp and the sun smiled as the Slovak Roman Catholic Church of St. Michael the Archangel was dedicated by the Rt. Rev. Msgr. James Garvey, Rector of St. James Church in Philadelphia, acting as the Delegate of Archbishop Patrick Ryan.

The little church could accommodate 260 people independent of the choir's seating capacity. During the day, ten beautiful stained-glass windows bathed the interior in natural illumination. A marbleized altar filled the sanctuary. Life-sized statues of the Blessed Virgin and St. Joseph adorned the two side altars. The interior walls were neatly frescoed, and the altar railing was of yellow pine with walnut trimmings. This church, completely furnished, cost $5,200 and was an ornament to the neighborhood and a testimonial to Fr. Heinen and his parishioners.

Until they settled in Lansford in sufficient numbers and constructed their own church structures, Greek Catholic (Byzantine) and Polish immigrants either attended the Slovak devotions or celebrated their own liturgy in the Church of St. Michael. The steady influx of Slovaks to the community necessitated the addition of two side chapels in 1893. At the same time, a steeple was erected and three bells were purchased and installed in the belfry.

On Thursday, February 21, 1907, the frame church, the fruit of hard labor and many sacrifices, was destroyed by fire. Within an hour, the small church was a mass of charred ruins. From that sorrowful day, the parish had to utilize the parochial school building, dating from just the previous year, for their services of divine worship. St. John the Baptist Byzantine Catholic Church, located just across the street, offered the use of their church to celebrate the Holy Liturgy, which was gratefully accepted. Years later, when the Byzantine Church suffered the same fate, St. Michael's Parish reciprocated.

Present "Cathedral - Style" Church of Granite Built:

Wasting no time, on February 24, 1907, after Sunday Liturgy, the then-Pastor Fr. Joseph Kasparek called a meeting of the congregation to discuss the question of building a new church. It was decided to erect a church of stone. With funds seeded by insurance from the former church, on February 27 the parish purchased property from James McMichael which measured 60 by 150 feet. It was situated immediately north of the first site. On Memorial Day, 1908, the cornerstone, inscribed "Rim. Kat. Slovensky Kostol, Sv. Michala 1908-Roman Catholic Slovak Church, St. Michael 1908" was laid by the Most Rev. Edmond Prendergast, Bishop of Philadelphia. The officiating prelate was escorted from the Lansford train station by a mile-long procession formed by the parishioners and Slovak Catholics from throughout the region. At the time, the construction had progressed to the completion of the basement, where the Mass was celebrated while the remainder of the church was being built.

The construction of the church, which began in 1907, was completed by Thanksgiving Day, November 30, 1911. On that day, the new edifice, truly one of the most beautiful in the Archdiocese of Philadelphia, was dedicated by the late Archbishop Edmond Prendergast. The church, Gothic in design, is built of Gouverner, New York State gray dolomite marble in broken range.

Stretching from Abbott to Water Street, St. Michael Church is 150 feet deep and 60 feet wide: the transept measures 84 feet across. Original seating capacity was 1,100 worshipers. The lofty steeple is 169 feet tall with an attractive electrified timepiece set by the E. Howard Clock Co. Within the belfry are three bells, christened St. Michael (weight; 3,000 lbs), St. Stephen (1,500 lbs), and St. George (750 lbs). The mechanism was designed so that St. Michael strikes off the hours, St. George the quarter hours, and St. Stephen chimes the Angelus. To summon the faithful for Mass, all 3 bells were originally rung by hand ropes, but now are electrified.

For the next five decades during which St. Michael Church was in the Philadelphia Diocese, for obvious reasons it became known affectionately as the "Cathedral in the coal region." The parish was incorporated into the Diocese of Allentown when it was established by Pope John XXIII on January 28, 1961, from the Northern Philadelphia Archdiocesan counties of Berks, Carbon, Lehigh, Northampton and Schuylkill.

Priests, Religious and Pastors:

From 1891-1894 and 1895-1903, St. Michael was a mission-chapel attached to St. Joseph Church in nearby East Mauch Chunk, where Fr. Heinen was the pastor. Pastors who served St. Michael Church since its founding:

Rev. Joseph Kasparek (1894-1895, 1905-1912)Rev. Peter Schaaf (1903-1905)Rev. Paul J. Lisicky (1912-1955)Msgr. Joseph A. Baran (1955-1978)Rev. Joseph D. Hulko (1978-1982)Rev. Thomas A. Derzack (1982-present)

St. Michael Parish boasts a total of 33 ordinations to the priesthood and 59 women who have entered the religious life.

The Carpathian Connection would like to thank Mr. David Kuchta for his continued support of TCC. Mr. Kuchta has spent years not only researching mines in the state of Pennsylvania but also working in them. Mr. Kuchta’s vast knowledge in this field has made him a celebrated author of numerous essays and works. Thanks Dave! The Carpathian Connection would like to thank Mr. David Kuchta for his continued support of TCC. Mr. Kuchta has spent years not only researching mines in the state of Pennsylvania but also working in them. Mr. Kuchta’s vast knowledge in this field has made him a celebrated author of numerous essays and works. Thanks Dave!

Courtesy of Stephen Miller

Courtesy of David Kuchta

by, David Kuchta

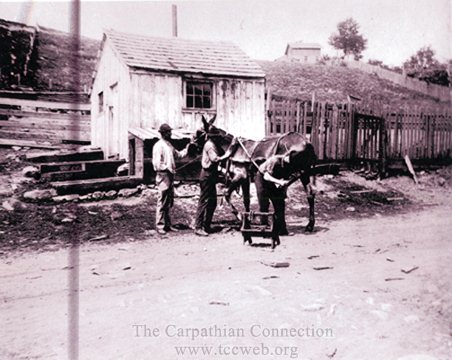

During the early years here in the Panther Valley there were two words that originally brought fear into the hearts of miner's wives: Black Maria! Around the coal collieries during and after the turn of the century there was a black covered wagon that was pulled by a team of horses. In later years this was a motorized vehicle that was later known as an ambulance.

During the mid to late 1800s, when people would see this "Black Maria," coming up the street, it brought shudders to those wives of miners who knew that just maybe, they were bringing home their husband or son. In those days, they used the "Black Maria," both as an ambulance as well as a hearse. If there was a bad accident at the colliery, a loud whistle would sound the alarm. But, if it was just what would be considered an average mining accident the whistle wouldn't be sounded. Just as in modern times, the word would get out that someone was killed and everyone thought the worst. Many of the local kids would see the "Black Maria," coming up the street and would be running along side or behind it like a procession. By this time the wives of the miners would be waiting or watching on the front porches or stoops hoping that the "Black Maria," would pass on by. Many of the wives would be praying the Rosary or silently wording desperate suplications to heaven.

During these early years, miners that were seriously hurt were taken by horse and carriage up to Ashland Pa. This was over very rough roads and was a long trip. Many a miner probably died from the rough ride or because of the length of time it took to get to Ashland Hospital. In time, trolley lines were in place from Mauch Chunk to Pottsville, Pa. This did help considerably. Then around 1910, the Coaldale Hospital was built and this was a real blessing for the local coal miners.

But before these trolley lines or Coaldale Hospital was built, everyone had to depend on the "Black Maria" to bring home their loved ones. Probably, the exasperating part was that the miner could be still alive but critically hurt. If the mine officials thought that he couldn't make the trip up to Ashland, he would be taken to his home for his wife to make him as comfortable as she possibly could for the short remainder of his life. If the miner was dead, they would place him on the front porch of his home. At this time, friends or neighbors would come over and take the body into the house, clean, dress him in his finest suit and prepare the deceased for his wake.

Just a few years ago, I always thought that the "Black Maria" was a local expression that was only used in the Panther Valley area. Then I started reading other books on coal mining throughout the entire hard coal regions, and saw this same words used for their ambulance or hearse throughout the entire coalfield regions. This term, "Black Maria," got me thinking about where these words originated. I thought that being the early years of mining here in Pennsylvania were done by Welsh miners that perhaps the word originated in Wales. How wrong I was! When I did research into this question about the use of a horse and carriage or vehicles called a "Black Maria," to haul the critically hurt or dead miners, I found that they used it during the Great Depression in the communities located in the western prairies. I found that it was something like an adaptation of the Model T Ford, and was used for transporting the deceased. Then, a good friend of mine came to the rescue and solved the problem of where the words, "Black Maria," originated. The "Black Maria," was the black van, which conveys prisoners from the police courts to jail. The French called it a mud-barge or a "Marie-salope." The tradition is that the van referred to was so called from Maria Lee, an African-American woman, who kept a sailors' boarding house in Boston. She was a women of such great size and strength that the unruly sailors stood in fear of her, and when constables required help, it was a common thing to send for Maria, who soon collared the refractory (person resisting control or authority) and led them to the lock-up. So because of this, a prison-van was called a "Black Maria." In time it was also used to describe an ambulance and a hearse.

by, David Kuchta

When I was a pre-teen, I used to go for haircuts with my father to George Swider's barbershop in Lansford, PA. The barbershop was first located at Patterson and Sharpe and then at his residence on East Bertsch Street. Since Swider was a fire boss at one of the Lansford Coal mines, a lot of mining went on while waiting for our haircuts. Sooner or later the subject of "boot-leg," mining became the topic. To those who don't quite understand the phrase bootleg mining¼it was usually a small mine operated by two to five workers. These were non-union and were built on property that didn't belong to the miners. In plain English; it was an illegal mining operation.

During the late 20s and early 30s during the "Great Depression," many miners were out of work and started their own bootleg hole. Many a family was raised on the money earned at these enterprises. Also, if it was not for the bootleg mine holes many homes would have been without heat during the winter season. Union miners had a love/hate relationship with "Bootleggers." If the miners worked, they couldn't care less, but if the legal mines were shut down or on strike the "Bootleggers" sold the coal cheaper and ran their operations on a shoestring. Most wouldn't pass a State Mine Inspectors rigorous inspection. They also didn't pay into the "Health and Welfare Fund." The locations of these illegal mine operations were kept secret. Any roads to the operations were kept camouflaged with branches, etc. Most of these mines were slopes driven on a steep pitch. The hoist motors would be the back axles of old cars or trucks hooked up to rigging that hoisted a small bucket or barrel, up and down the slope. Most of these buckets or barrels were pulled up on wood skids. Not too many used rails and small railroad wheels in their project. In the bigger mining ventures the car or apparatus to pull up the coal to the top of the tipple was a "gunboat." Most of these operations were in Schuylkill County on Reading Anthracite Coal Property. The larger coal companies went after the bigger veins of coal and didn't bother with the five or six foot veins.

The Coal Companies knew the approximate location of all the coal veins way back in the 1800's. The state had entire coalfields all explored and mapped out. In the larger valleys with mountains on both sides of it, it is not uncommon to have up to eight larger veins of coal running in an east, west direction. These same veins are located on both sides of the valley. The veins go deep down, under the valley and then come up the other side. Like I had said, most large operations didn't go after the smaller veins until after the mines had closed down and "strip-mines," became more popular. Some of the larger veins were from eight to ninety-feet thick with some forming a roll action and being over 150 foot in width. These were the Mammoth Veins and were the most popular veins to be mined. During the hay-day of mining, the larger mine corporations could have up to eight levels of mine operations below the bottom of the valley. When these mines were in operation, large pumps were used 24 hours a day to keep the water out of the working areas. It is a fact that about 20 tons of water had to be pumped from the mines for every ton of coal. So you can see that the expense is quite high in deep coal mining. Plus, all the mine water that is pumped out of the mines must be treated. The environmental expense is staggering.

The boot leg mines or smaller independent mines can't afford large pumping expenses. In this day and age there are only a few bootleg operations existing. There are many independent mines that sign leases with the landowner to mine coal. They either pay royalties on a ton of coal or sell all the coal that is mined to the owner for a predetermined price. These independent mines fall under the regulations of the State and Federal Government and are inspected by State Mine Inspectors. The smaller bootleg operators try to drive a slope in the vicinity of old workings. This way they drain all the water into the old mines. Of course there is always danger from the old workings because of cave-ins or even water accumulating in old gangways and breaking into new mines. Down through the years, many a bootleg miner lost his life in these illegal operations. All mines are charted and the state knows where old workings are located and were the pillars were robbed. Well usually! I have a friend who had one of these bootleg mines. It was in a part of the mountain that hid the operation from the landowners but some local bikers found the mine and supposedly reported it to the authorities.

The State Mine Inspector that checked out this mine was impressed with the way it was driven but when he received a complaint about them he had to shut it down. If my mind remembers, he blew it shut with dynamite and then had the local contractor come up with one of his bulldozers and doze it shut. In this case, the mine was a safe operation but was illegal as far as the landowners were concerned. Today, some of the smaller veins are mined with small buckets on a drag line shovel. I also would imagine that with today's helicopters and snoop planes, the illegal bootleg mine operators will be a thing of the past. If there are any of these illegal mines in operation in this day and age¼they are kept a secret!

by, David Kuchta

When mining started in the Panther Valley, injured miners were taken to local doctor's office. If he was hurt extremely bad, the injured was hauled to the miners home, deposited there and left to the miners wife to make him as comfortable as possible during those last hours of his life. An interesting thing is that they used the "Black Maria," wagon to deliver both the injured as well as the dead miners to their homes. When people saw the "Black Maria," coming up their street, they thought the worst. During the later years of mining in the Panther Valley, badly injured miners where taken by horse and wagon all the way up to Ashland State Hospital. The roads were in terrible shape, and if the injured miner was hurt seriously, the ride there usually did him in.

During early 1900, streetcars were utilized to haul the injured to Ashland or Pottsville. The ride was much smoother but it still took too much time to reach their destination. Because of this distance from Ashland or Pottsville hospitals, the Coaldale Hospital came into being. In 1909, the miners of the valley volunteered a full days pay for the construction of a hospital while the Lehigh Navigation and Coal Company through the efforts of the Superintendent Ludlow, donated a site for the building. The Coal Company also told the miners that every dollar they donated; the company would also match that amount. The location of the hospital was east of the village of Seek. The hospital would overlook the valley and was built in a very pristine area. This area was where John Moser had built his first home, which was the very first home in the area, which became known as Coaldale. The building was completed on July 11, 1910. The contributions amounted to $50,000. The structure was a three-story brick building and was originally built to accommodate 30 patients. The hospital soon averaged 68 patients. The hospital was divided into three wards; two for men and one for women. Because of the congestion, every available room was utilized at all times. Later, they enclosed the two large porches on the south side which gave the hospital eight additional beds.

In 1911, the interior of the hospital was destroyed by fire. All patients were taken to nearby houses to be treated. Luckily, the homes were empty at the time. Throughout the years, the hospital has been in continuous operation. In 1934 the majority of the patients were miners of the valley, and that there were more surgical cases presented than medical cases. In the men's ward at one point of time, there were a large number of broken limbs, nine of which were suspended from slings, swung from overhead. There were also a large number of burned patients. One was a survivor of the Foster tunnel entombment. At the time he was in the hospital suffering from burns sustained in the mine explosion. The laundry, laboratory, and dispensary are located in the basement. The dispensary, which is quite small for the work being done, has about 80 patients per day. A modern X-ray machine, classed as one of the best for those early years, a modern kitchen with all the latest equipment and complete refrigerating plant were all added. The first nurses in the hospital were; Miss V. Kazakewica and Miss Nellie Close. The first patient admitted to the hospital was Stephen Snikschak from Lansford who was admitted on July 14, 1910. In time new wards were added for burn victims, women and children, including an isolation ward and corridors. Being that the original capacity of the hospital was 30 beds, there wasn't enough beds for new patients so 10 more beds and six cots were crowded in, allowing scarcely enough room between each bed for a nurse to attend the patients.

When possible the overflow was taken care of by placing two patients in one bed, and other are asked to sleep on the floor with blankets. To eliminate this problem, the Board of Trustees limited the class of patients admitted. Because of this some patients had to go 25 or more miles away to other hospitals. In time the board had to recall this order. Dates of new buildings are the following; the original building was built in 1909, the new annex, in Sept. 1927, and the nurses' home in 1933. The employees originally numbered 15 and in 1934 numbered 59. The bed capacity was originally 30, and in 1934 was 92. John Prostovich of Poland, was the first man to die in the hospital. The opening of the new maternity department was in January, 1932. The first child born there was Daniel Conahan of Seek, born on January 1, 1932. In 1927 ground was broken for the Nurses Home. For some reason work on the building ceased in 1929 when it was almost completed. Probably because of the Great Depression, things like this were curtailed. This building stood vacant until 1933, when the Board of Directors managed to cut all the necessary red tape with the State Department, and then preparations were made for its occupancy. I hope you have enjoyed the trip back into time.

by, David Kuchta

Just what do we know about the history of coal mining. When did it start? Where and how did it evolve down through the years? Frankly, I don't think too many of us have the faintest inclination about the history of coal and coal mining. I also don't think that anyone under the age of 40 remembers seeing our coal breakers or even hearing the high shrill whistle of the small coal mine "Lokies" going through the valley. These are sights and sounds that will never be seen or heard again. The younger generation and baby boomers probably never saw a coal miner walking to the lamp shanty in gum boots, face and clothes all blackened by coal dust! This is all part of our mine heritage, but only a small bit, because there is so much more to know. Before I got involved with the No. 9 Mine and Museum, I was just like everyone else. I read and heard how mines were damp, dark, deep, dusty and at times dangerous. It was also drummed into me by my father, that I wasn't going to end up working in a mine like him or my grandfathers. With five years of doing research and also working every weekend in the No. 9 Mine, I have learned a lot about the history of mining. When the old timers spoke, I listen! When I wrote my book, "Once A Man, Twice A Boy," I interviewed quite a few old time miners. But instead of researching the run of the mill information I researched out other information about horseplay, pranks, cheating by the company and the miners and also about kickbacks to the fire bosses. This kind of stuff wasn't discussed no less read about. I'm continually learning a lot about our coal mining past. I also enjoy writing about it and preserving this heritage for future generations.

When I went to school, many moons ago, the teachers drummed into us kids that Philip Ginter discovered Anthracite coal in Summit Hill in 1792. They made it sound like this was the first coal every found in the State of Pennsylvania, or as far as I was concerned the world! I soon found out that this discovery was strictly only for Carbon County, which doesn't take in too much area as far as coal mining is concerned. Anthracite Coal was already discovered in parts of Wyoming County (which at that time was a part of the large Northampton County.) To get a better idea of when and where the first coal mines were, I will try to give a break down through the years about the finding and use of coal. The very first coal mined that is recorded was coal that was mined during the Roman Occupation of Britain in 55 BC to 436 AD) along the banks of the rivers Clyde and Forth. Later in Britain coal was mined by the monks of Holyrood and Newbattle Abbeys in Scotland and also by the monks of Northumberland. In 1215 coal was mentioned in the Great Charter of King John Here is an interesting tidbit about coal mining. During King Edward’s reign (1239-1307) he imposed the death penalty to anyone using coal because it was believed that it gave off, "poisonous odors." That bias against the use of coal lasted for about two centuries. Most of us "Coal Crackers" think that the first coal discovered in America was in West Virginia or Pennsylvania. Sorry, not so! The first coal discovered in America was in 1673 near present day Utica, Illinois. This is credited to Louis Joliet and Jacques Marquette. It was also Benjamin Franklin who converted a fireplace that he had invented in 1741 to burn coal and subsequently invented the coal stoves that burn both Anthracite as well as Bituminous Coal. Although most of us senior citizens know what went on above the ground, so little is known what went on underground. We know so little about the profession of "coal mining." Coal mining wasn't just a hit and miss type of venture. Most mines were well planned and engineered. The coal companies knew were the veins of coal were located but when it came to inclines, rolls or pitches this was something that was found out when the tunnels and chutes were driven.

The surprising part of our coal heritage is that there is literally millions upon millions of tons of coal (some recoverable, some not) still in the ground after all these years of mining. Most of the easy (getting) coal is already mined. What is left are huge deposits of coal deep in the ground. Under Pottsville is the huge mammoth vein, which is from 100 to 200 feet wide. But with present day technology it is impossible to mine. The vein is 2,000 feet down. The biggest problem would be the expense of mining it along with removing all the water. Years ago they had to pump 20 tons of water for every ton of coal removed. With no concerns on river pollution this wasn't a problem but now with strict environmental laws this water would have to be treated and cleaned before being pumped back into our streams. The Mammoth Vein of coal is also under the Panther Valley, along with the other various veins of coal. In the future with more modern technology and better systems of mining, this coal may be mined. Of course, if a better way of mining and more economical and more environmental friendly fuel is discovered (such as Hydrogen) then the coal will stay where it is forever. Just knowing that the coal reserves are still there in the ground does put us in a more advantageous position over other countries around the world where there coal reserves are gone or where oil reserves are slowly getting depleted.

by, David Kuchta

On September 27, 1915, eleven men were entombed in the East Mammoth Vein of the Foster Tunnel. It was a water level opening of the Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company, situated on the Southwest boundary line of the town of Coaldale, Pennsylvania. A sudden rush of water from the East Mammoth top split gangway, an abandoned working area, entombed the 11 men for six full days. According to LC&N records, the 11 men were: four contract miners, two laborers, a battery starter, a loader, two mule drivers and a door tender who were involved in driving the chute that eventually flooded. It might be well to note that the East Mammoth top split gangway of Fosters tunnel had been worked and the breasts broke through into the East Mammoth top split gangway. The water, which closed the bottom split gangway, came from these breasts. No trouble was ever experienced with water problems in any of these breasts. In Chute No. 24, the water broke through at eleven o'clock on the morning of September 27 after a shot had been fired by William Watkins and Gint Hollywood, two competent miners, who were engaged in driving, the slant chute.

Both men managed to work their way amid the water and debris down the chute to a crosscut into and up No. 23 chute where they were entombed for 22 hours. The volume of water that broke through made its course from the old gangway, down No. 24 chute gutting it out as the water went along. The water broke down the pillars of coal between chutes Nos. 24 and 20. It violently eroded the No. 20 breast, which was enlarged three times its normal size. From there, the water and debris went down No. 20 chute into the gangway and then proceeded toward the mouth of the tunnel. In its course the water picked up timbers, rocks, coal and fine material, to close and compact the gangway from No. 19 chute to No. 25 chute. This distance is approximately 300 feet long. Upon being notified of the accident, General Inside Superintendent W. G Whildin and Mine Inspector I.M. Davies immediately went into consultation and under their supervision, rescue parties and plans for re-opening the gangway were promptly formed and put into immediate operation. Three rescue parties were formed and definite work assigned to each. One party was to make a narrow opening on the top of the gangway, and another party was to open the airway or monkey gangway and the third party was to follow the first party into the mine for re-opening the gangway to its full width.

It is reported that 150 workers took part in the rescue efforts. The party, which was opening the gangway to its full width, started at the No. 3 chute and cleaned up such materials that were carried by the water in its course toward the tunnel mouth. The rescue party, which worked the upper lift of the gangway, started at chute No. 19 and opened a hole 3 by 4 feet along the south rib (Wall of the tunnel.) This work was tedious and slow due to the extreme difficulties which were encountered along the gangway. Between chutes No. 20 and 21 the progress was impeded by striking a steel mine car and truck that was caught in the flood-waters. By means of an acetylene torch, enough of the mine car was cut away to permit the men to follow the north rib and proceed with the rescue work. At the time that the men were rescued, this rescue party had advanced very close to chute No. 25 where the mules were found amid the old timbers, rock, coal and other debris. The rescue party which advanced along the airway started at chute No. 19 and proceeded on to No. 20 where it was found that the pillars of coal had been washed away leaving No. 20 breast almost three times its normal size.

Three sets of timber, well planked, were used in crossing this breast and the rescue party advanced along this airway. The coal pillars between chutes Nos. 23 and 24 were badly damaged and extra precaution was used in opening this area. When reaching chute No. 26, black damp, CO2 was encountered and it became necessary to use a supply of compressed air to drive it out in order that the work might continue. Chute No. 26 was the first chute found opened and after driving the black damp gas out, the men explored the chute to its mouth and found the gangway filled with water. Two electric pumps were used in lowering this water and when sufficiently lowered, a raft was built and further explorations in the gangway began. On Oct. 3rd, John Humphries, the foreman at Foster's tunnel while on the raft, shouting as he went further into the mine, made contact with Elmer Herring. Elmer Herring who was the strongest of those imprisoned, came down the chute where the men had taken refuge. Herring yelled, "My God man, turn your light the other way, it is blinding me." Humphries asked Herring how were the other men? "All alive!" was Herrring's response. Subsequently, Herring led Humphries to the rest of the men huddled in Chute No. 27. At chute No. 27, the men were found all alive and in good physical condition. A temporary platform was built along the legs of the gangway timbers and each entombed man, after being trapped behind a wall of water, timber and loose coal for six days and five hours, was slid along this platform to chute No. 26. They went up the chute and along the course which was opened by the rescuers to chute No. 20 ½. Then, they were taken down the cute to the gangway where the company physician gave them hot coffee, and when necessary, a hypodermic injection to stimulate their weakened hearts.